- Home

- Christine Coulson

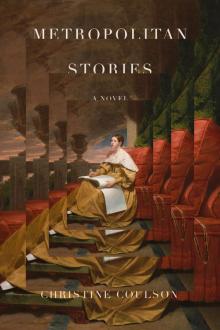

Metropolitan Stories

Metropolitan Stories Read online

PRAISE FOR

Metropolitan Stories

“Stories define museums, and none more so than the Met. But it takes imagination as much as knowledge to recognize and appreciate them, as Christine Coulson’s enchanting novel reveals. Melding fact and fiction, art history and autobiography, her strange tales of mutually dependent artworks and caretakers beat with a pulse that oscillates between the real and the unreal, the ordinary and the extraordinary. More than any scholar or connoisseur, Coulson’s exquisite book captures the essence of the Met—its ability to delight, surprise, astonish, and, ultimately, to dream.”

—Andrew Bolton, Wendy Yu Curator in Charge, the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute

“Every painting, every tapestry, every fragile, gilded chair in the Met not only has a story, but gets to tell it, in Christine Coulson’s magical book. The history, humor, wonder, and—perhaps above all—beauty that Coulson absorbed in her twenty-five years at the museum burst forth from these pages, in her wry and imaginative tales of the people and objects that make the Met all that it is.”

—Ariel Levy, The New Yorker staff writer and New York Times bestselling author of The Rules Do Not Apply

Copyright © Christine Coulson 2019

Production editor: Yvonne E. Cárdenas

Text designer: Jennifer Daddio

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

For information write to Other Press LLC,

267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Coulson, Christine, author.

Title: Metropolitan stories / Christine Coulson.

Description: New York : Other Press, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019007798 (print) | LCCN 2019000107 (ebook) | ISBN 9781590510582 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781590510636 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.)—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3603.O885 M48 2019 (ebook) | LCC PS3603.O885 (print) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019007798

Publisher’s Note: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Ebook ISBN 9781590510636

v5.4

a

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

We

Chair as Hero

Musing

Meats & Cheeses

Gift Man

Night Moves

Mezz Girls

Lost

Adam

Big-Boned

Found

The Talent

What We Wondered about Alexander Ferris

Where We Keep the Light

Object Lesson

Papercuts

Acknowledgments

For Philippe de Montebello,

Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1977–2008

And for all the extraordinary people

who have devoted their lives to our beloved museum

You are my heroes.

WE

We protect them and save them and study them. After a time, we realize—some of us slower than others—that they are protecting us, saving us, studying us.

“We” are generations of golden children, thousands of staff members, raised by the Metropolitan Museum, put in its ward and shaped and stretched until our eyes can spot beauty like we’re catching a ball, quick and needy, clutching it to our chests so it is ours, all ours.

Our knees buckle as we learn every one of the museum’s tangled paths—every gallery, every limestone hall, every catwalk and shortcut, every stairway up and down and across and over—until our muscles, tutored and trained, always bend us in the right direction.

We dream of chalices and Rothkos, African masks and twisting Berninis unfolding in our minds like so many fluttering pages. Our hearts stutter with their stories, so many stories that words won’t do. We need to show you what we see, what we have woken up, right here, right now, in this shiny box.

“They” are the objects, the art, the very stuff of the place. The things the public comes to see and longs for us to sing about, loudly and clearly and with every breath, until the visitors are too inspired, too tired, to see another bronze, another altarpiece, another sword or portrait or vase. After buying a bag of proof in the shop—a sack that says the museum has been done, with Van Gogh napkins to prove it—the visitors leave.

We and the objects stay. We have our evenings to cling together and our mornings to reunite. We connect like neighbors across a fence, one side always knowing more; we like to think it’s us, but it’s them. Our hungry scholarship scratches for what they’ve already lived. Those objects were there, saw the whole thing, right in front of them. Watched the tomb door close, pinching the sunlight until it narrowed to one last blinding stripe, then thrrump! Gone.

We depend upon their magic, know it like a quiet superstition. The objects glide into our world—once fixed, now moving—each time showing up somewhere we did not expect. Because we did not realize that we needed to be rescued by marble and silk, or canvas and oil paint, or charcoal upon a page, pushing beyond gilded frames and glass cases to reach out and do with us what they will, always for good. Never against us. Those works of art work—to make the right things happen and sweep the wrong things down the steps of the museum in heavy drips that collect and wash away. And we are breathless and relieved to have the art on our side. It is why we never leave.

CHAIR AS HERO

Sometimes I wish we had a support group. We would start by introducing ourselves.

“Hi, I’m a fauteuil à la reine made for Louise-Élisabeth, Duchess of Parma.”

The other chairs would immediately think I’m an asshole, particularly the older Windsor chairs.

Everyone would know that I still have my original upholstery and that I’ve made cameo appearances in a few minor paintings. There’s some cred in that, but also a lot of resentment.

I remember back in Paris when a master carver sculpted me into coils and tendrils, decoration so florid that even my smoothest surface arched into acrobatic movement: swinging, reaching, bounding, wrapping with wisteria determination.

Gold leaf coated each of these spiraling forms. The sheets of the precious metal, impossibly thin, floated onto my exposed wood like a soft rain, cool and tender. Silk velvet was then stretched across my curves, a fine, bespoke suit, taut and precise, with glistening ornament along its edges.

I can picture Louise-Élisabeth’s daughter, Isabella, age eight, on the day I arrived from France at the Ducal Palace of Colorno in Parma. It was 1749, and she stroked my crimson velvet with such care, trying to appear grown up and sophisticated.

But I also remember when she curled herself within my arms and cried fat, messy tears, her knees tucked tightly beneath the panniers of her gown with its flowers and ribbons. I can still feel the heaving of her chest against my back as she shivered gently to the rhythm of her sobs. How I wish I could have swayed along with that pulsing

sorrow to comfort her.

Only five years later, Isabella’s siblings, Ferdinand and Maria Luisa, would topple into me during audiences with their parents and pull at my gold trimmings, as clumsy and silly as any children, despite their finery.

One time at the Met, a small boy—not more than three years old—wandered past the barriers in the Wrightsman Galleries and headed straight for me. Almost two hundred and twenty-five years had passed, but he reminded me so much of those toddlers back in Parma.

Come on little guy! I thought from behind the gallery ropes. You can make it!

The boy’s plump hands extended forward, propelled by his thick, tumbling waddle, his shoes clomping on the gallery floor. I felt like I was hanging from a cliff waiting for him to grip my arm and save me. Then a breeze of moist heat floated past as his mother grabbed him at the very last second—just before he reached me.

That was 1978. I still dream about it. I imagine the boy climbing up onto my seat. His pleasant folds and warm, springy pudge nestled between my arms. A small puddle of drool soaking into my velvet, the life of it racing through to my frame.

I would share those dreams in the meetings.

Of course, I remember the lonely attics and warehouses, too. Rooms of swollen heat and shrinking cold. Dark, hollow, airless. A desolate purgatory, despite the stacked and crowded landscape, a bulging mountain range of the stored and forgotten.

In the brittle stillness, dust showered down upon me with a fragile constancy, like some gray and final mist, ashen drifts accumulating on my every surface. For decades, I ached for the feel of footsteps rattling through the floorboards, quivering up my legs, delivering some—any—faint agitation of life. And oh, to be the chosen one when that door finally swung open, the chooser blackened against the blaze of ripe and glorious light!

Storage would definitely come up in the meetings, too.

Eventually I landed back in Paris at Maison Leys, the city’s foremost interior decorating firm at the turn of the century. There, in 1906, the legendary connoisseur Georges Hoentschel sold me to the American giant J.P. Morgan, along with two thousand other pieces of furniture. Morgan gave the whole lot of us to the Met, where I will always live in great splendor.

But Parma was my home. I will never forget the light and shadow of those glorious rooms of my youth. Some days I trace every detail in my mind, the way prisoners do to survive captivity. I feel Louise-Élisabeth’s body collapsing onto me, tired and alone: the fearless daughter of a king, frustrated by her timid spouse and hindering lack of beauty. I can still smell the sour odor of her flaccid husband as he picked at my gilding.

Little Maria Luisa eventually became Queen of Spain after she was engaged to her cousin Charles at age eleven. Short and not as pretty as her older sister, her feet swung lazily from my edge as she listened to her mother explain the arrangements of the loveless marriage. As rebellion or consolation, a parade of lovers would later sink into my velvet during Maria Luisa’s reign.

Maria Luisa kept me with her until she died in Rome in 1819. I held her through the fear and tragedy of twenty-four pregnancies over twenty-eight years. Only six babies survived.

I wouldn’t talk about those memories in the meetings.

MUSING

The briefing memo was clear: “Mr. Lagerfeld will bring his Muse. The Muse will not speak. Do not address the Muse.”

Michel read the sentences twice. He did not relish the idea of meeting with a fashion designer, but found himself curiously admiring this particular detail. It had been a long time since anyone had truly surprised him. He wondered why he himself had never thought of such an accessory.

Michel’s twenty-eight-year career had been marked by the acquisition of every stylish trapping: a baroque desk, volumes of art books, handmade suits each punctuated by his small, red Chevalier lapel marker. But a Muse. Ah, the cleverness of bringing a Muse to a meeting. Michel took the eccentric gesture as both an invitation and a challenge. As the Director of the greatest museum in the world, he could surely scare up a Muse by tomorrow.

Maybe an attractive curator, he thought to himself, his mind racing through the staff to inventory the possibilities. Rather paltry, he smirked. Didn’t it use to be different? He remembered a time when the Met seemed to be riddled with alluring women targeting his handsome affection. Had the gay men taken over? Or did he just not notice as much anymore?

The Drawings Department had an intriguing brunette researcher, and that Italian decorative arts curator always made him think of eighteenth-century French novellas about sex and exquisite furniture.

That startlingly good-looking woman in Finance would do. He always felt a minor frisson when she rode the elevator with him. Astonishing legs, even in flat shoes—which he never liked. He had been known to summon her for a spurious budget question on a slow afternoon. But even he would be hard-pressed to justify her attendance at a meeting with a fashion designer.

Lily Martin would be there, but the Museum’s President, while striking, functioned more like a sister than a Muse. She didn’t have the right éclat—and there was certainly no telling her not to speak.

Eleanor would figure it out.

“Elllleanooor!” he bellowed in his signature baritone, “I will need a Muse for my meeting with Karl Lagerfeld tomorrow.”

“Of course,” Eleanor replied without enthusiasm. She occupied a gray cubicle outside Michel’s office and, after twenty-four years as his assistant, very little could get her out of her seat, least of all his demand for a Muse.

“We’ll need someone raaaavishing.” Michel continued, still shouting from inside his office. He prolonged the pronunciation of the last word with particular thrust.

Again, Eleanor was unfazed. Unlike Michel, she skipped any consideration of the staff and went right to the art. Plenty of Muses there. Surely they could ask a Muse from the collection to attend an hour-long meeting.

She remembered when the figures from Rembrandt’s self-portraits abandoned their paintings and came over to the office to hold Michel’s hand through his sixty-fifth birthday. That was a long day. Eleanor never told anyone about the sobbing she heard behind Michel’s door as he confronted that milestone. You wouldn’t expect Rembrandt’s old boys to be so empathetic, but they sat with him for hours. They understood Michel’s vulnerability—had felt it all before themselves—and misery does love a little camaraderie.

Eleanor wouldn’t mention that, historically speaking, a Muse does the picking, not the other way around. This detail need not apply to Michel Larousse, who tended to be self-inspired. She understood him well enough to see that this project was an amusement, a mildly competitive way of making a fashion designer look foolish by participating in his charade.

She also knew that Michel was getting tired in a more fundamental way, and that these spasms of some central, fading self were a way of holding on. She looked down and slowly shook her head, thinking of a former curator’s description of Michel many years ago: “He just loves to be that special boy.”

* * *

—

The scramble began. There were things that Michel did not care about (the public, unattractive people, American art, the Education Department) and those that were critical (European paintings, beautiful women, the rich, the absence of oregano in any meal). A showdown of Muses would fall definitively into the latter category and would be subject to a connoisseur’s rigor.

An unspoken requirement was that the Muse not outshine her inspiree. Certainly, great beauty was required, but there were limits. The selected Muse would be strumming her lyre for a man with a special spotlight in his office that subtly illuminated him in his chair. She should be an exceptional ornament, but could not divert attention from the Director himself. It was a delicate balance.

Eleanor started by calling the Greek and Roman Department to see if this task could be dispensed with quickly. They immediately sent up The Th

ree Graces. But the Graces were naked, headless, and inextricably linked together, so she sent them back. They shuffled out clumsily, the stuttering steps of the conjoined, silent in their headless disappointment.

Eleanor knew the collection held plenty of Muses—a popular subject throughout art history—so she flexed the power of the Director’s Office and had a junior assistant hand-deliver an urgent memo to the heads of all seventeen curatorial departments:

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

INTERDEPARTMENTAL MEMORANDUM

TO: Curatorial Department Heads

FROM: Eleanor Rock, Director’s Office

RE: Urgent Request

January 26, 1998

It has come to our attention that the Director will need a Muse for a meeting tomorrow. Please send all applicable candidates to the Director’s Office by 10:30 AM today. Beauty and condition should be strong considerations in your selection. Thank you.

Eleanor was fully aware of the chaos she was igniting. Before long, the Director’s Office looked like a production of A Chorus Line. Muses of every stripe, stroke, and stipple crowded the waiting area and spilled out into the hallway, gathering in confused clumps, many creakingly stiff, frozen in their original poses. It had been a long time since they’d moved.

Some departments stretched the definition of Muse quite radically, but many of the collection’s Muses could be traced back to the original myth of Zeus’s nine daughters, each inspiring within a particular discipline: Calliope (epic poetry), Clio (history), Erato (love poetry), Euterpe (lyric poetry), Melpomene (tragedy), Polyhymnia (sacred poetry), Terpsichore (dance), Thalia (comedy), and Urania (astronomy).

“I hear this guy’s a real creep,” one Melpomene sputtered.

“Really?” an Erato responded, tuning her lyre. “I heard he’s hot.”

“A total god,” chimed in a Polyhymnia.

Metropolitan Stories

Metropolitan Stories